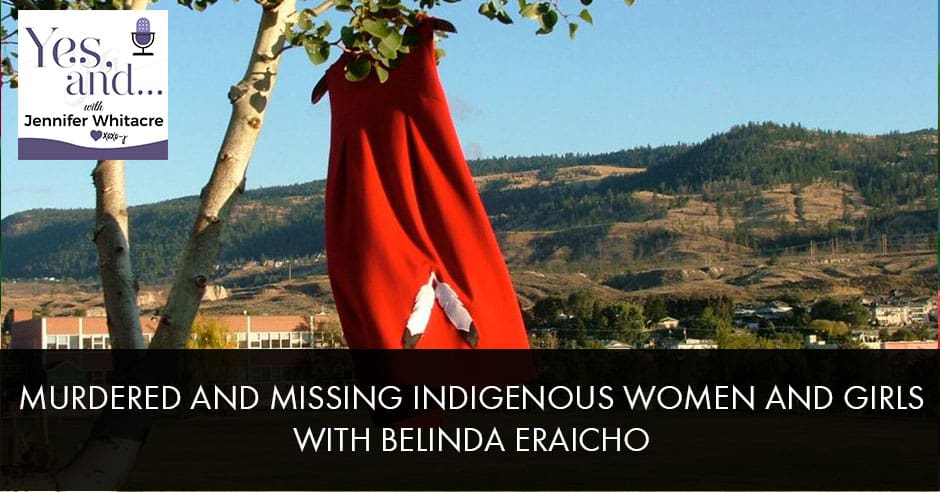

Murdered And Missing Indigenous Women And Girls With Belinda Eraicho

In today’s society, it is alarming how crime and murder incidents are continuously rising. Every day, we see news flashes on television of people who have either gone missing or were murdered. In this episode, educator and healing practitioner Belinda Eraicho joins host Jennifer Whitacre in taking a good look at the murder and missing cases of indigenous women and girls. Belinda also talks about the REDress Project and how it’s bringing awareness to these issues.

Watch the episode here:

Listen to the podcast here:

Murdered And Missing Indigenous Women And Girls With Belinda Eraicho

I am with Belinda Eriacho. Belinda was on my show once before. Belinda comes from a lineage of Diné and Ashiwi, which is known to us in white peoples’ languages as Navajo and Zuni. She’s located in the Southwest United States. After a long professional career, she decided to give back to her communities by sharing her cultural traditions and life experiences. We’re taking a little bit of a different stance because last time Belinda was here, we talked about ancestral healing and intergenerational trauma. We are going to talk about giving voice to our murdered and missing indigenous women and girls. We’re going to talk about The REDress Project. We’re doing this because November is a National American Indian Heritage Month. This was implemented back in 1990 by George W. Bush. Even though it was implemented in 1990, there are still a lot of people who don’t realize that November is a National American Indian Heritage Month. This is the perfect time to talk about this. There’s a lot of trauma in these communities and this is a discussion worth having. Belinda, welcome back to the show. It’s an honor to have you with us again.

Good day, Jennifer. Thank you so much for having me on your podcast again. I’m looking forward to the conversation. You already indicated that this is Native American Heritage Month. It is an opportunity for us to bring voice and to educate the public about issues that are impacting Native people across the country, but also first nations people in Canada. I thought that this would be a great opportunity to bring this issue forward. One of the things before we begin this conversation, Jennifer, I’ve been in preparation for this show. I’m thinking about the families and the women that have gone missing or murdered. I want to remind everybody that let us not forget that each of these women and girls that have been murdered and missing are someone’s daughter, someone’s sister, someone’s mother, someone’s grandmother, someone’s friend and someone’s loved one. My point here is that there’s a human being behind it, each and every one of these statistics that we will be talking about throughout this show. Thank you.

I am in total agreement. I would like to point out to our readers too that there are people who are missing in all cultures. We need to bring more awareness to some of our minority cultures because it’s not more important in one culture. It’s not more important based on skin color, race, heritage, where you’re from, what your background is or what your genetics say you are. The pain is universal whenever it comes to this. The suffering and trauma are universal. It’s time that we come back together and do something about this instead of stay separate. There’s way too much separation among the different races and cultures right now. The REDress Art Exhibition was started by a woman named Jaime Black. Belinda, can you tell us a little bit about this REDress Project and what that is?

Jaime Black is a Metis artist in Winnipeg, Canada. One of the things that she was trying to do is to bring attention and awareness to the missing and murdered Aboriginal women in Canada. Part of her project was to collect 600 red dresses through community donations, which she was able to do. Through this medium, she was able to exhibit them in public places like parks, universities and museums to bring this awareness to the forefront. Her main goal was to draw attention to the gendered and racial nature of violent crimes against Aboriginal women. It’s a visual image that you can see. I indicated that it was displayed throughout Canada. Here in the United States, it was also displayed at the National Museum of American Indians in Washington, DC. There’s a YouTube video that folks can take a look at and watch to get the significance. Even though you may not know these women and these girls, it brings your attention to this big issue.

I understand that the exhibition has been brought to the United States and in a couple of other locations as well to bring more awareness. The movement has only three art exhibitions at this point. Cornell is one of them. There have been three of these art exhibitions in the United States. It’s starting to grow awareness, not just in Canada, but it’s also starting to filter down to us here in the States.

The significance of it is red is a very sacred and powerful color in indigenous cultures. Her whole idea was that the red dresses were to call back the spirit of these women and girls whose lives were lost or who have gone missing. That’s the significance of the red. That’s one of the questions you had raised in the last show that we had together.

You said red is very sacred. Is there a deeper meaning to the red in the sacredness?

If you look at it, a lot of indigenous people, there are typically four colors that represent the four sacred directions. There’s either turquoise or blue, there’s red and there’s white. In the original teachings, those were the colors of the original people. Red is significant to the red people. In some cases, that was where the term Redman came from, it is to signify the indigenous people of the world. Red is also a representation of fire in a lot of cultures. It’s the essence of the fire element. It is a powerful color and it has much significance.

Can you give us a little bit of information on what has transpired in Canada, as it relates to the murdered and missing indigenous women and girls?

I will do my best to do that. There are many details and facets to this whole unfolding of this story. I want to apologize in advance for some of the details that I may leave out, but I wanted to give you an overview of what has happened. In Canada, did you realize that they never even had a database for missing people until 2010?

I didn’t know that.

That is ironic. I’m going to walk you through in some historical events that have happened.

Is it missing people in general or is that missing ingenious people?

Missing people in general.

That is astonishing to me.

In 2011, there was the first Canadian report that came out. It was covering a period between 1997 to 2000, which was a three-year period. What they determined was that the rate of homicide or murder of Aboriginal women was seven times higher than other females in the area that are non-indigenous or non-native people. In 2013, the Commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police initiate studies to try and identify how big of an issue this was. There was eventually a report that was issued in 2014. In that report, the main statistics that came out of that, there were 1,000 indigenous women who were murdered over a 30-year period of time. The number of indigenous women who were victims of homicide increased 9% of all female homicide victims in 1980 to 24% in 2015. This was almost an increase of threefold. The other statistic that came from this was that from 2001 to 2015, a fourteen-year period of time, the homicide rate for indigenous women in Canada was six times as high as opposed to the non-indigenous population.

There’s another report that got issued. As a result of all of this, in 2016, because of all of the indigenous groups, the activists and others who are concerned about the incidents of murdered and missing women, it was brought to the attention of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. He established a national inquiry into this issue. There’s a whole other conversation around the statistics. When you get into the statistics that were reported by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, one of the things you had to keep in mind that those were the only cases that were reported and typically only where the Royal Canadian Police patrol the area. We’re talking about the rural indigenous communities that were not even non-existent. To me, these statistics are not showing the truth or telling a true story of what has happened.

That threefold increase is probably much higher.

As we go through the rest of the unfolding of this story, it gets pretty interesting. At the very end, I want to do a comparison between what has happened in Canada and what it has happened in the United States because I’m starting to see that there are some parallels in a different context.

I understand that some of these murders were associated with a particular highway. It’s been referred to as the Highway of Tears. Can you talk about that a little bit?

The Highway of Tears is a term that was given to a stretch of Highway 16 that runs from Prince George to Prince Rupert in British Columbia. The phrase is based on a 1998 vigil for four murdered and two missing women initially. One of the things that happened over time was that there were nineteen women that were killed on this particular stretch of highway. In addition, there were also 49 women from the Vancouver area who were murdered by the serial killer. I don’t know if you remember the story. The murderer’s name was Robert Pickton. He was a pig farmer. There’s a whole other story that is around that whole issue.

I do remember that story.

There’s a big disparity as we’re going through these statistics between what has the police are reporting and what the government and indigenous communities are finding their own real experiences that are happening. On this particular stretch of highway, on the Highway of Tears, it was estimated that there had been more than 40 murders and missing women. A book came out and it is called the Highway of Tears. In that particular book, it goes into each of these stories of these women and these girls. Some of these girls were as young as 14 and 15 years old. It is a tragic story. My point was there’s a big gap in the numbers due to who and where they were being reported at.

What are some of the reasons why they’re not reporting?

As I’ve started to read some of the materials and read through some of these experiences, first of all, I want to bring up the point that a lot of the issues stem from colonialism. You put people into a reserve or a reservation and they’re trying to make a living and be all economically independent. One of the things that happens is there are a lot of social ills that go around that, particularly on that highway. One of the things that you find is that a lot of indigenous communities, whether first nations in Canada or native Americans in the United States, we don’t always get a lot of the public services that other people get in an urban area. For instance, public transportation. One of the main reasons that a lot of these women and girls were on that highway, in particular, some of them were going to go see family members. They would get on the road and hitchhike. They needed to go to school. They needed to work in the next community. Those are some of the reasons why they were there. They were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

This is something that I can speak to. I understand that some of these were not reported because some of the girls might have had some interactions or been in trouble with the law. As a trauma specialist, people who are traumatized are more likely to have interactions and be in trouble with the law than people who are not dealing with trauma within themselves. A lot of times, the acting out behaviors become distorted and we’re more likely to take risks and think that you have problems with authority. You do things that would be considered illegal or risky behaviors. There’s a lot of trauma in the indigenous and Native American communities too, and that holds people back then. I don’t know if that’s completely related to any race because I see it in other races here in the United States where people who are traumatized, other minorities, even in rural, poor white areas. There’s more likely to have crime and issues with authority in some of those more traumatized areas.

Some of the stories, as I was reading through this particular book on this particular highway, it talks about some of these young people who had a run-in with law enforcement. When they went missing, the assumption by law enforcement was that they were out with friends partying or they were doing something or being in a place where they shouldn’t have been. In a lot of these instances, it wasn’t until 3 or 4 days, sometimes a week or two weeks, that even though the family kept on trying to go to the police to file a missing person’s report, they didn’t honor that. The other thing that you’ve got to think about too is if you’re a young person, you’ve already been in trouble with the law and something happens to you tragically, whether it’s an abuse, physical abuse or sexual abuse, the last thing you want to do is go to the police and report that. There are a lot of the reasons why there’s a lot of under-reporting, not only in Canada but also in the United States as well because we have the same issue on a lot of our reservations.

You talked a little bit about what’s going on in Canada. What were the results of the inquiry by the prime minister?

Interesting enough, after the report came out on June 3rd, 2019, there was a group of Commissioners that went through this report. At the very end of this summary, one of the commissioners said in the report and in public that this was an epidemic “a Canadian genocide.†Buller, who was Head of the Commission, went on to further state that there’s an ongoing deliberate race identity and gender base, a genocide. They recognize that there was a big issue with this. The report further went on to say that, “We convey truths about state actions and inactions rooted in colonialism, colonial ideologies, built on the presumption of superiority and utilize to maintain power and control over the land and the people by oppression and in many cases, by eliminating them.†That was some strong points. There were two separate reports that ended up resulting from this inquiry. There were over 700 recommendations that came out of this. From my understanding, there are only a few that had been implemented.

Genocide is a strong word to use in something like this.

Coming from a group of independent commissioners, that says a lot. One of the interesting things is because of the change in the leadership that the policyholders from the time that this report was issued to who now runs the political offices. That is from my understanding the reason why a lot of these recommendations have not been implemented. Some don’t feel that it’s important enough. One of the things as an indigenous person, as a Native person, that’s the story we always hear is, “It’s not important. You’re not important enough.†That’s some of the themes that I will share with you as we go through the rest of this show.

The colonialism or you could even call it the power-over paradigm, that’s not just an indigenous problem here. It’s a worldwide problem for indigenous people around the world where this power over has come in and tried to force their way of life on the people who already lived there before they came. We’ve been seeing in the last few years that that doesn’t work. There is this grassroots push for cooperation and collaboration, whereas there are still people in power who are still trying to force the power over instead of letting the cooperate and collaborate the way we want to.

One of the things that you mentioned as we started was that we all need to live on this same planet together and we need to learn to get along with each other. I started to read a book, White Fragility. It was interesting. It’s an eyeopener for me because it’s so foreign to me. Not too long ago, I was with a friend of mine. I was asking her to explain to me what’s white privileges because from my viewpoint, I don’t have any concept or understanding of what that even means. As I started to read this book White Fragility and one of the aspects, I encourage everybody to read it. It’s an eye-opener because it gives you a whole other perspective of our history, not only here in the United States and in Canada, but around the world and how there was this need to conquer to take land for wealth. It’s gotten us to this point was it absolutely nowhere. That’s one of the other points I wanted to make. I encourage folks to read those books as well.

It’s important to understand the history of our own race and as well as other races. The last time you were here, we talked about ancestral and intergenerational trauma. If you don’t understand where you come from, a lot of times, you don’t understand the motivation for why you do what you do and why you treat other people the way you treat other people. Those of us who hail from Europe, we have a long history of fighting amongst ourselves. We are not being able to get along with anybody. That’s the truth. There’s a long history of white people not being able to get along with anybody. We have to go in and conquer. We fight amongst ourselves in our own families. We don’t have a lot of cooperation within the family unit. It is important to understand that if you’re ever to overcome that trauma.

I’m sure that you’re feeling this as well, that there’s a big shift happening around us. The truth about the things that were not always very truthful are coming out. The more of that I think is going to start to unfold itself, including what we’re talking about the racism and the whole historical aspect that relates to all people.

If we can understand, if we can start to read a little bit more about indigenous peoples and how there was an early tribal culture. A lot of cooperation, collaboration and cohesive units, where people lived peacefully together, that helps us understand, as white people, where you’re coming from. If you can understand the fragility that helps us understand where we’re coming from, then we can start to work together.

It tells all the learning experiences. You’re not going to come across as I’m angry or upset. I see it as an opportunity for us to learn and work together.

None of us is like the power over paradigm. I think that part of the white fragility is white people are starting to see other people rise to power. They don’t know what to do with it. They see that as a threat and it isn’t. To see it as a threat speaks to our trauma and speaks to where we come from, and not what’s happening in the world. It’s simply a cultural interpretation of what’s happening in the world, which doesn’t make it right because that’s how you interpret it. Everybody interprets it differently.

Jennifer, let’s shift gears. Let’s talk a little bit about what’s happening in our own backyard here in the United States.

That’s what I was getting ready to do. Thank you.

One of the things that I shared a little bit about in our last show was about some of the statistics related to the violence of indigenous women here in the United States. Indigenous in a sense that, I used synonymously with Native American, American Indian and Alaskan Natives. We’re all the same. The statistics from the CDC, which is the Center for Disease Control, reported that murder is the third leading cause of death among American-Indian and Alaska Native women. In addition, violence on reservations can be up to ten times higher than the national average. If you can imagine that. To me, it says that even me as an indigenous Native person, I am a part of that statistic. It makes me vulnerable. It’s a risk that I have to take when I go out into the community.

The other statistic that was interesting is that 84% of American Indian and Alaska Native women have experienced intimate violence from their intimate partners, sexual violence or stalking. This was a statistic that came out of the Department of Justice in 2016. There are also 50% of American Indian and Alaskan Natives who have experienced sexual violence in their lifetime. This was all from the same organization. The statistics go on and on. It’s on some reservations. The murder rate is ten times higher or even higher because of the points that I made. A lot of it is under-reported or just as it goes unreported, there are a lot of issues related to that.

I understand that there are jurisdiction issues whenever there’s a murder on a reservation. Can you talk a little bit about some of those jurisdiction issues and how is that a problem?

Before I get there, while we’re talking about statistics, there is something that I wanted to share with you. There’s an organization called the National Crime Information Center, which is the database that is used by criminal justice professionals here in the United States. One of the things that was interesting as I am looking at this report was that there were a little over 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women, girls and women, only 116 were logged into this database.

What’s the timeframe for those missing women? Is there a time period?

The time period that they looked at was in 2016. It was just one year. What happened to the rest of the 5,596? Don’t they matter? The story goes on and on that’s similar to this, which is tragic.

That’s heartbreaking. That’s beyond tragic.

One of the other statistics that we have even touched on is the urban Indians. They were in all of our major cities across the country as part of the assimilation process policy. Historically, a lot of Native people ended up moving into the cities. Either forcefully or voluntarily, to find a better quality of life whether it was to find jobs or to get educated. There are a lot of statistics around that. Across the country, when you talk about major cities, there are 128 missing person cases, 280 murder cases and 98 unknown cases. The follow-through is not consistent. That’s the thing that I’d been talking to you about. Interesting enough, I’ll read to you the top five cities where these issues are happening. These were happening in Seattle, Albuquerque in New Mexico, Anchorage in Alaska, Tucson in Arizona and Billings in Montana. Those are the top five cities where you have a lot of similar issues going on.

There is something to be said about that and they need to fix those databases and the reporting process for murdered and missing women and girls. To answer your question about the challenges around law enforcement, there are challenges and barriers related to accessing information from law enforcement agencies, especially for communities and tribal nations and policymakers in order for them to understand how big of an issue it is. They need to have that data. Sometimes that data is not always available because either they weren’t keeping track of them. In some instances, some of the evidence was disposed of. There’s no way to go back and look at that.

Part of the issue is that here in the United States, we have an issue with regards to jurisdiction. If a white male ends up murdering a Native American person on a reservation, the local police force, the tribal police do not have jurisdiction over that because that was the way that the law was written. They have to elevate that to the federal level, which in our case and here in the United States is the Federal Bureau of the Investigation or FBI. When you think about what’s on their plate, if it’s one murder on our reservation versus a big crime that’s happening somewhere else, chances are, the focus is going to end up going to the bigger issue and not so much going into looking at this investigational issue on the reservation. Where this stems from is there was a Supreme Court case that happened in 1978. The Supreme Court ruled that tribal courts do not hold any jurisdictional power over Non-American Indian and Alaskan Native, therefore, they cannot prosecute or punish them for their crimes. That’s one aspect. The second aspect is that in 1968, through the Indian Civil Rights Act, it limits the maximum punishment for any crime to $5,000 and one-year present time. There are these loopholes in the system that do not allow for justice to take place for these families and these victims.

That’s mind-blowing to me that somebody who’s not a Native American could go onto a reservation and commit murder and nothing could happen other than $5,000 and a year in prison.

When you’re putting in the time, you can understand from a Native American woman’s perspective, “If I’m raped or violence has happened to me from a non-Native person, what’s the point in even reporting it?†As either, they’ll get thrown out of court or nobody will do anything about it.

Most women can relate to that because most women in this country, it doesn’t matter what race we are, if we’re raped, we have a hard time reporting it. We know the rape case is going to sit there. We know that nothing is going to happen, but this is a whole other layer of why bother? It’s heartbreaking and astonishing to me. It’s a whole other layer that I wasn’t even aware of.

When I look back at all of the pieces of information that I went through from all of these experiences in Canada versus what’s happening in the United States, there are a couple of themes that I see. The quite obvious one is the lack of reliable and consistent reporting of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls. That’s the biggest problem. The other thing is reporting only occurs in certain areas where law enforcement is active. If they’re out in a rural reservation somewhere, chances of it being reported are none. The other thing that I touched on was colonialism. There’s a big social condition for first nations of Native Americans as a result of colonialism of indigenous people that we need to understand because when you bring a people down, you put them in poverty and they never have an opportunity to care for themselves, it sets up a whole set of barriers for them.

It’s like the women on the highway. They didn’t have access to any public system. Now, they started running a bus line through that area, but it’s not consistent enough. It’s subsidized. If you’ve got people that are in poverty and they have to choose between getting on a bus, paying for a ticket to get on a bus versus putting food on the table, what are they going to do? They’re going to put food on the table. You don’t set things up for Native people or indigenous people that be successful from the get-go. That’s one of the other biggest issues that we have. Here in the United States, there are some initiatives that have been happening to try and bring this issue to the forefront.

Here in Arizona, there was a Bill No. 2570, which established a committee to do a comprehensive study of how big of an issue this is here in a state of Arizona. I know that there are some other states that are being proactive and looking at that. You may be familiar that in 2017, Congress approved the Savanna Act. Savanna Greywind was a 22-year-old pregnant member of the Spirit Lake Tribe, who was tragically murdered in 2017. As a result of that, this particular Bill or Act was put in place. I put in place some of the initiatives to drive and try to get the Department of Justice to move on some of these issues, including providing training for law enforcement agencies of how to record victims into their federal database. That’s a key. Develop and implement a strategy to notify citizens of different systems that are out there and available to them, conduct outreach to different tribes so that they can become educated us what to what they can do as they try to help and protect their women, but also develop guidelines for response to missing and murdered cases as well.

There was a whole list of actions that came from this. In addition, there are other things that are happening in different communities. There’s a young lady who was seventeen years old. She’s from the California area. She wrote a play, which is called Men Kneel and Her Heart. She’s dedicated this to murdering indigenous women. For your readers that happen to be in that particular area, I know that she has a show that’s going to be happening on the 17th of November, which is coming up in the Santa Bernardino, California area. There are other things that are happening. There was a quilt that was donated or given to the governor of the state of North Dakota. He’s trying to raise awareness of this issue in his community. It was a way for him. He had paid a visit to some of the reservations. I try to understand what some of the social issues were and to give him a better context of why this was important. I think some of our leaders need to get out. They need to get out from behind their desk and know what’s going on out there in their communities. That’s the other issue that I see.

One of the points that I kept bringing up is there’s a bigger issue here. We touched on it about colonialism and racism. It’s something that we cannot look at it sometimes because of either our own history with our ancestors or for some other reason or experience that we may have had. It’s important that if we are going to coexist as human beings on this planet, we need to understand and look at those issues. Even if it’s uncomfortable, that’s where the growth and the healing begins.

You can’t heal unless you go through the discomfort of feeling the pain and feeling the discomfort of the pain because that is part of the healing process. These difficult conversations about our racist tendencies, that has to happen for healing to occur.

One of the things as I look at these types of issues like intergenerational trauma, I look at our own history here in the United States, I look at this issue of murdered and missing indigenous women and girls, I couldn’t help but go back and look at our original documents of this country like the constitution. If you go back and you look at the Fourteenth Amendment, which is the Equal Protection Clause. It states that, “Nor shall any state deny to any person within its jurisdiction the Equal Protection of the laws.†For me as an American, as a Native person, that’s not true because I don’t see that happening in our communities. We’re not protecting our women. We’re not protecting our girls. Because of the way that the system has been set up, it doesn’t allow us to be successful.

This is a whole other layer because in many cases, women across the board are not protected. I’m not sure that there is awareness and I’m grateful that you came back on the show to bring awareness to this. I don’t think there’s enough awareness as to how vulnerable women are in minority cultures, especially Native American indigenous and Alaska Native cultures.

I’m glad that you’re doing this as well. The media has a big responsibility in getting this information out. It’s interesting that some of the stories that I read through and as much as the families tried to go out and reach out to the community to do get the radio stations, to get the word out that they’re missing a loved one, a lot of times they were refused that. In one instance, it was in the Vancouver area. There was a young lady that went missing and within 24 hours, it was a massive media blitz. All of the news stations had her on TV or posting her pictures. Unfortunately, when it comes to indigenous people and Native American people, we don’t get that attention, which is the responsibility of the families to go out and doing their knock on the doors, print their posters. I think the media also has a big role in this. They have a big responsibility. I understand also that when it comes to the national news or the local news, that they have their own pieces of information that have to be presented, but at the same time, those things are people’s lives that are as important. The Native American lives, the first nations’ lives is important as well.

I’m not sure if the media are ever going to hold themselves accountable. The media are scripted and they’re told what to say. We don’t have investigative journalists to the extent that we used to have back when I was a kid. We don’t have Walter Cronkite and Dan Rather anymore. We have people who read the news and they say what they’re told to say. I would hope that people would start to take personal responsibility for where they consume their news. Let’s stop turning to the mainstream news because it’s all scripted. It’s fear-mongering. It’s meant to keep us divided. It’s a lot of opinions and people talking back and forth. We have a saying where I come from, it’s like opinions and assholes. We all have them. It doesn’t mean yours is any more relevant than mine.

It’s true. Your opinions are no different than mine, no better than mine or no worse than mine. It doesn’t make mine more relevant. If we all would take personal responsibility and start looking to where the real news is coming from, a lot of times there’s more real news that comes across from live feeds of people out in the streets during protesting. Like, “This is what’s happening in my city,†or what we’re doing right now, to report what’s going on. I would hope that people will start to take personal responsibility. You’re a force to be reckoned with, Belinda. Thank you so much for raising awareness of these issues and talking about them. That’s how we’re going to do something about them is to have people talk about them and to have awareness of it.

It’s not an easy thing to name a lot of these issues in our society that are broken. There are issues that cause tension between different races, which is the whole race subject is a whole other story when you read where the word race comes from and how we started as a nation and as a global community, how we started separating who was white. It’s fascinating when I read through some of the history about how did these terms come about? Who was behind him? Who decided who was brown, who was black and who was white? Going back to the point about the media, it is an issue of integrity. It’s personal and a professional ethics issue that you have to live with yourself. If you’re a reporter or if you’re a news anchor, you have to live with yourself in terms of are you in it for the money? Are you in it for what you originally had planned to go to school for, which is to report the truth?

What are some of the actions that people can take individually? What do you recommend?

There are a couple of things. I had mentioned some of the different projects that are happening like The REDress Project. All of the exhibitions that this young lady puts out there is all through donations. You can put and make an investment there and get the word out that way. This is a start to educate yourself on the subject and get involved. You can also get involved by participating in your legislative process if you happen to be in one of those states where this is a big issue. There’s a lot of bills and legislation that’s going to look to the leadership for approval to help. First of all, identify how big of a problem did we have then provide the resources to teach changes pictures that we continue to see.

There are also marches. One of the things that I do every year in the springtime is here in Arizona, we have a march for the murdered and missing women. I go out there and I march with everybody else to help bring awareness that this is a big issue. We need to take care of one another. Media has a big play in all of this. We can all get up there as I’m doing and make our voices heard for those that don’t have a voice. There needs to be some resolution to a lot of these stories. It breaks my heart when I read stories about a 14-year-old or 15-year-old. She never had a chance to live her life to its fullest. Those are the situations that we have to deal with.

I would also like to add that for the average person, you’re talking about people as young as 14 or 15, teenagers, young women, look back at your life. For all of our readers out there, did you make the wisest decisions when you were 13 or 14 years old? When I was a teenager, in my early twenties, I can’t count how many times I put myself in situations that I look back and I’m like, “I was stupid. Why did I do that? Why did I go there? Why did I think that was okay?†If you look at the development of the brain, we are hardwired when we are teenagers. We’re going through all these hormonal changes and we look at how the hormones affect the brain. We look at brain development. Our cortex or cerebral cortex is not fully formed. It’s not fully functioning until our mid-twenties. That’s for men and women, both. For women, it is somewhere around 22 to 24 years old. For men, that’s about 24 to 26 years old.

When you have a not fully formed cerebral cortex and hormones pumping through your system, you are hardwired to make poor decisions. Why would we vilify anybody for their physiology? Some of these girls had run-ins with the law. That happens in all cultures. Why vilify one race over another for the same exact behaviors? We need to start calling a spade a spade and saying, “We all do it. We all make poor decisions. Let’s not vilify one race over another. Start to have compassion for everybody. Start to have justice for everybody and treat everybody like the human beings that we all are.â€

One of the other things that is important, for this particular issue, there’s a long history. We have an opportunity to learn from all of that where we are right now. If we don’t learn, we’re going to repeat it again as we have done in many other things in history. It’s an opportunity for us to work together. We have to live on this planet together. Let’s start somewhere.

Another mistake that we as the colonial race has made is we have labeled minorities as savages throughout history for centuries. There was a study I learned about this from Dr. Gabor Mate in a class that I’m taking with him right now. There was a study at MIT or Harvard, where they have determined that the ideal scenario for raising children, so you have healthy, happy, trauma resilient children are pre-colonial Native American, indigenous tribal cultures where there are about 75 to 100 people. He even says that there was one particular tribe that would say for the first two years of life, their babies’ feet never touched the ground because they’re held so much and they’re loved so much. They’re coddled. There’s so much attention given to the children that they have secure attachment. It gives that strong foundation. If you look at the truth, who’s the savages? We’ve got to go back and re-look at history from a different angle, from a different perspective and stop believing that our perspective is the only one that’s correct because research is showing differently.

It’s interesting you mentioned that because if you go back to our constitution for the United States, it specifically mentions the savages there. If we are going to change the context of who we are as Americans and reunite again, that’s the first place we need to start. We need to remove that because it doesn’t have a place at this time.

It was propaganda in 1700. That still has filtered through epigenetically to today. Belinda, this has been such a powerful conversation. Thank you so much for coming on the show again to raise awareness. You’re a force to be reckoned with and I appreciate you so much.

I appreciate you, too. Thank you so much, Jennifer, for allowing me to bring this topic to the forefront.

Do you have any final tips or bits of wisdom to leave with our readers?

One of the things that I wanted to leave everyone with is as you start to learn about these particular topics, please understand that each number that you read through, each statistic that you read through, like I said, someone’s daughter, someone’s sister, someone’s mother, grandmother, loved one. That puts a human being to each of those numbers. We’ve forgotten about that. We need to get back together as a human race to understand each other and to lift each other up instead of trying to bring each other down. That’s my wisdom. Thank you so much, Jennifer.

Thank you, Belinda. For all of our readers, if you want more information about Belinda, visit her website, Kaalogii.com. That’s where you can find more about Belinda, services, events and you can find her blog and everything that she does. If you want more information about me or my podcast, go to JenniferWhitacre.com. That’s where you can find more information about me, my services and the Yes, And Podcast. I will see you all next time.

Important Links:

- Belinda Eriacho

- Show – Belinda Eriacho’s previous episode

- The REDress Project

- Highway of Tears

- White Fragility

- Kaalogii.com

- https://Kaalogii.com/about/

- http://www.TheREDressProject.org/

- https://www.Amazon.com/White-Fragility-People-About-Racism/dp/0807047414

- https://www.Amazon.com/Highway-Tears-Jessica-McDiarmid/dp/1501160281/ref=pd_sbs_74_2/131-1989135-0564325?_encoding=UTF8&pd_rd_i=1501160281&pd_rd_r=3f8fb403-b66a-4c7e-be28-6ea1debe3efd&pd_rd_w=pOWqg&pd_rd_wg=yPy63&pf_rd_p=52b7592c-2dc9-4ac6-84d4-4bda6360045e&pf_rd_r=AA0M290P9TJ740Q0WCEA&psc=1&refRID=AA0M290P9TJ740Q0WCEA

About Belinda Eraicho

Belinda Eraicho comes from a lineage of Dine’ (Navajo) and Ashiwi (Zuni) located in the Southwest United States. After a long professional career Belinda decided to give back to her communities by sharing her cultural traditions and life experiences.

Belinda is bringing awareness to the REDress Project, an art exhibit by Jaime Black that’s bringing attention in the United States and Canada to the disproportionate numbers of murdered and missing women in Indigenous communities.